© 2023 House of Health. All rights reserved.

Web Design by Netbloom

Web Design by Netbloom

Iron is an essential nutrient for all organisms. It has a number of important functions in the human body related to transport and storage of oxygen, hormone manufacture, DNA replication, oxidation-reduction reactions and antioxidant effects. Iron deficiency is a global issue and is thought to impact more than two billion people worldwide (Rusu, 2020). In New Zealand/Aotearoa, estimates are that around 1% of men, 10% of women, 15% of children are iron deficient (Grant, 2007). While even marginal iron insufficiency can impair proper functionality, too much iron has a major impact on the liver and the composition of the gut microbiota. And for many, taking extra iron results in painful constipation.

In short, No. Low iron stores (measured by blood ferritin level) can occur before a person becomes clinically anaemic.

Iron deficiency anaemia occurs when there are low numbers of red blood cells, or low haemoglobin in those cells, due to insufficient iron in the body.

Without enough haemoglobin, blood cells cannot carry oxygen. Without enough cells, the same is true.

There are several risk factors for iron deficiency, which fall into 3 main categories: insufficient intake, poor uptake (absorption), and increased losses. Let’s look at each of these.

Iron is found in a range of foods, in varying concentration and differing forms.

Some types of iron are easier to absorb than others. Because iron is utilised in the blood and stored in the liver, food such as red meat and liver (e.g., “lamb’s fry”) contain the highest concentrations of iron, in the most absorbable form.

Spinach is very high in iron, but it is not as absorbable as the iron in animal products.

Excessive iron can be harmful. Check your needs before supplementing.

Mussels are also a very good source of iron. Some plants are very good sources of iron – for example spinach and parsley – but the form is less absorbable, which means more is needed.

Absorption of plant-sourced iron is increased by vitamin C – either dietary or supplemental – taken at the same meal.

Vegetarians and vegans are at increased risk of iron deficiency and should get a blood test regularly.

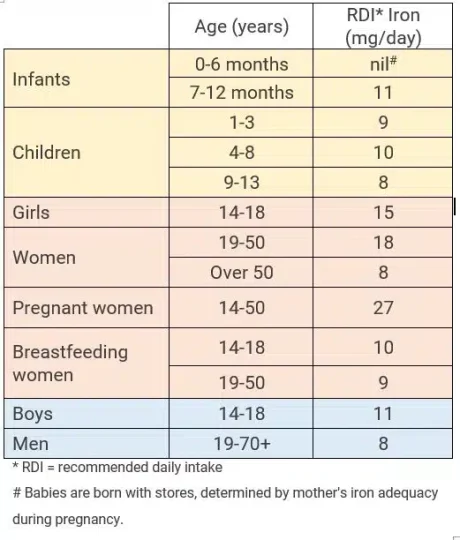

The amount of iron needed varies according to age, gender and life stage. For example, pregnant women need more than non-pregnant women, and babies are born at full term should have enough stored iron to get them through to starting solids, if the mother’s intake was adequate during pregnancy.

The absorption of iron in the human intestine is complex. In very high amounts, iron is harmful to the liver, so our capacity to absorb it is limited. When body stores get low, the ability to absorb iron increases. Reduced absorption is also associated with stomach infection with a bacterium called Helicobacter pylori (Fraser, 2010).

Some foods, supplements, and heavy metals can block or reduce iron absorption. Phytates (e.g., in wheat and wholegrains), and tannins, which are very high in black tea (with or without milk!), inhibit absorption, while lead and zinc compete for iron uptake. Consuming foods containing vitamin C and citrate (both of which are found in citrus fruits) helps increase iron uptake. Some probiotic-type bacteria can increase the availability of dietary iron due to changing its form (Rusu 2020).

Bleeding is the most common cause of iron loss. This can be hidden, such as bleeding within the digestive system, or heavy menstrual bleeding in women. More obvious causes of iron loss are donating blood, frequent nosebleeds, or trauma (BPAC, 2013).

Medicines (such as aspirin, voltaren® and ibuprofen) increase the risk of stomach ulcers. Stomach ulcers increase the risk of bleeding from the lining of the stomach.

Low iron levels in the blood in spite of adequate intake needs to be investigated to rule out iron loss from more serious conditions.

Anaemia has a direct impact on the quality of life. Because low iron causes reduced oxygen supply to muscles, organs, and tissues, there are a lot of different symptoms, that can result. These include reduced immune function (more likely to get infections, coughs and colds), fatigue, low mood, restless legs, reduced exercise capacity (easily breathless), heart palpitations, poor memory or concentration, loss of libido, increased menstrual flow, and pale skin (Nielsen, 2018).

After chewing, the next most important thing to aid the release of iron from food is stomach acid. Hypochlorhydria is low hydrochloric acid in the stomach, which is a risk factor for nutrient deficiencies, including iron (Kortman, 2014), because the acid helps to improve the solubility (and therefore the absorption) of iron. Hypochlorhydria can happen due to medicines that counteract or block stomach acid, or if there are changes in the function of the stomach.

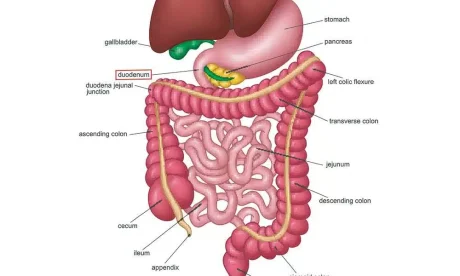

Dietary iron is absorbed in the first part of the small intestine (the duodenum and upper jejunum), so any condition the affects the normal environment there (such as coeliac disease) can interfere with iron absorption. A healthy microbiome is associated with good levels of substances called short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), which seem to increase iron absorption (Kortman, 2014).

Dysbiosis (an imbalance in gut bacteria) can also contribute to iron deficiency. Iron is needed for the survival and replication of almost all bacteria (Yilmaz & Li, 2018), which can lead to a ‘tug of war’ between the bacteria and the host for the available iron. If an overgrowth of bacteria exists in the small intestine, these bacteria may use the iron before it can be absorbed. Interestingly, reducing iron intake can reduce the growth of potentially pathogenic gut bacteria (Parmanand, 2019).

There are a range of gastrointestinal disorders, associated with dysbiosis, including diarrhoea, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and gastroenteritis (Kortman, 2014).

Taking supplemental iron to correct iron deficiency, or iron deficiency anaemia, often causes unpleasant side effects such as abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhoea, and nausea.

High dose iron is known to alter the gut microbiota, because unabsorbed iron travels to the colon (large intestine), supporting the growth and virulence of gut bacteria. If these are potentially problematic bacteria (e.g., Escherichia, Klebsiella, Listeria, Neisseria, Pasteurella, Shigella, Salmonella, Vibrio, and Yersinia), this may aggravate intestinal inflammation and associated symptoms (Yilmaz & Li, 2018 , Chieppa, 2018, Rusu 2020).

If you experience gut symptoms related to iron supplementation, it might be wise to do a health check of your microbiota. Checking for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) may be indicated, or it might be the colonic population that is out of balance.

Showing all 2 results

Herbal Medicine… is as old as humanity and the basis of modern medicine. Plants are our means of obtaining nourishment – either

House of Health Ltd

Due staff shortages, please use the website, phone or email to place your order. We will let you know when your items are ready for collection. Dismiss

Stay informed: Get expert tips, free advice, updates, recipes, and special offers delivered straight to your inbox.