What is Endometriosis?

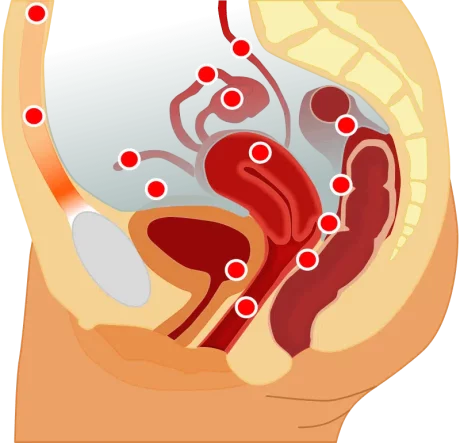

Endometriosis, thought to affect at least 10% of women of menstruating age, happens when there is endometrial (uterine) tissue growing outside the uterus. The most common sites are the ovaries, fallopian tubes, and around the uterus, but it may also be found on the bowel, bladder and other abdominal organs and occasionally as far as the lungs. It can range in severity from minimal, mild, moderate, to severe.

What are the Symptoms of Endometriosis?

Endometrial tissue is subject to the influence of circulating hormones, which fluctuate with the menstrual cycle. Although sometimes thought of as a ‘problem with periods’, the health issues associated with endometriosis are far more widespread. Pain is a common symptom, affecting up to 70% of those with the condition. Pain may range from mild and present only during menstruation, to extreme, debilitating, and can be chronic (constantly present).

Other symptoms may include painful sexual intercourse, bleeding between periods, infertility or recurrent miscarriages, headaches, fatigue, bladder problems such as pain when urinating, urgency and frequency, and bowel problems such as bloating, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and/or constipation.

While most women with endometriosis will suffer with some or all of these symptoms, a small percentage may experience no symptoms at all. If women have disturbed bowel function, it is important that they are evaluated for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

What Causes Endometriosis?

The cause of endometriosis is unknown. There are several theories with the most widely accepted being reflux of endometrial tissue into the pelvic cavity during menstruation (“retrograde” flow). However, up to 90% of women experience retrograde menstruation and a much smaller percentage develop endometriosis 3,8 indicating other factors are at play.

Influences on the development and maintenance of endometriosis may include genetics, oestrogen “dominance”, inflammation, immune system dysregulation, autoimmunity, and an altered gut microbiome.

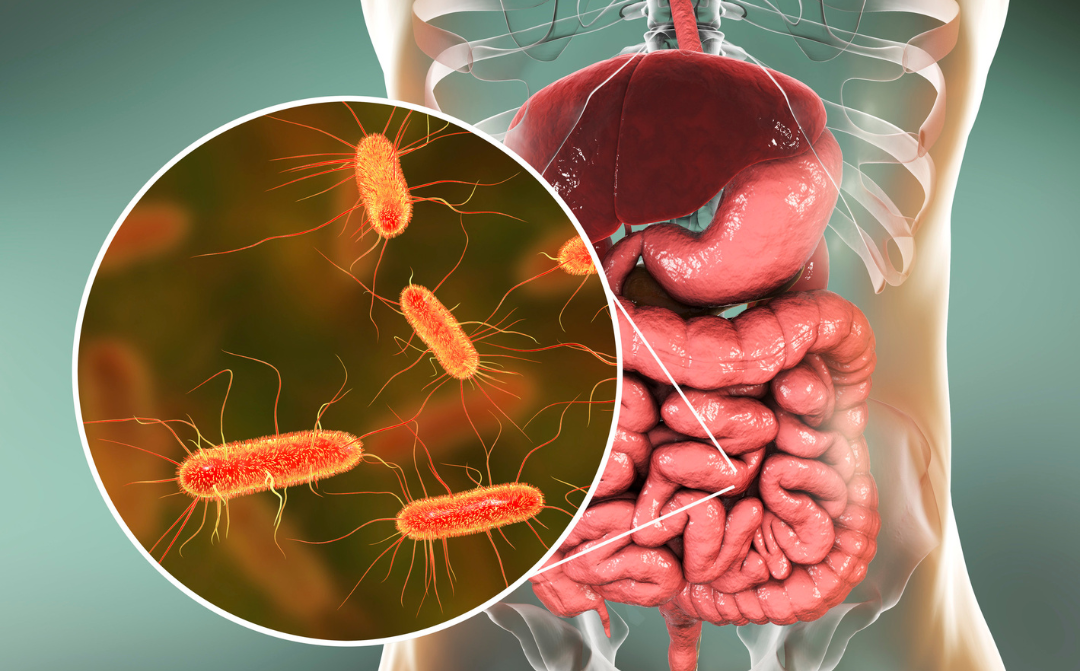

The Role of Gut Health and the Microbiome

Digestive health and poor gut function may contribute to endometriosis and vice-versa. Scarring and adhesions on the bowel and abdominal wall resulting from both the disease itself and the surgery used to treat it likely contributes to impaired gut motility and an altered microbiome.

Endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome have a number of overlapping symptoms (including increased pain sensitivity) and up to half of women presenting to gynaecological clinics have symptoms of IBS. Sadly, the hysterectomy rate in women with IBS is disproportionately, and quite possibly unnecessarily high.

Links between an altered gut microbiome and IBS are well established, and is a possible way the gut may influence endometriosis. Disruption of the gut microbiome (dysbiosis) can cause an imbalance of beneficial organisms and potential pathogens. This may occur due to many factors including antibiotic/antimicrobial treatment, prolonged periods of stress, as well as dietary and lifestyle factors. Collectively, a healthy microbiome is responsible for many vital functions including production of vitamins B12 and K, maintenance of a normal gut lining; preventing overgrowth of harmful bacteria; and ensuring a healthy immune system.

There are 3 different types of dysbiosis: a decrease in beneficial organisms; excess numbers of potentially harmful organisms; and a loss of overall microbial diversity. All three types have been noted to occur in women with endometriosis. Although it is not currently well understood whether endometriosis leads to dysbiosis or vice-versa, an association has been identified and is the focus of ongoing research.

Dysbiosis may influence the development and course of endometriosis due to the impact on:

- low grade, systemic inflammation, and impaired immune function,

- lipopolysaccharide (LPS) levels, and

- oestrogen metabolism.

Inflammation and Immune Function

The gut microbiome helps to maintain the structural integrity of the gut lining preventing intestinal hyperpermeability, commonly referred to as ‘leaky gut’. Gut bacteria produce nutrients such as short chain fatty acids and proteins that help keep the intestinal lining healthy. This, in turn, helps to prevent inappropriate movement of intestinal contents and bacteria through the lining where they could be a factor in wide-spread inflammation.

The last decade has seen an explosion of clinical studies demonstrating an association between dysbiosis and a wide range of diseases due to dysregulation of inflammatory processes and immune cell responses.

Lipopolysaccharides

Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) are toxins found in the cell wall of gram-negative bacteria that promotes the formation of endometriosis. Alterations to the gut microbiome often results in an imbalance favouring the proliferation of these LPS-producing bacteria. Multiple studies involving women with endometriosis have identified higher proportions of gram-negative Proteobacteria, with Escherichia coli being the best-known of this group. High concentrations of E. coli have been found in the menstrual fluid of women with endometriosis.

Oestrogen Metabolism

Oestrogen stimulates the growth of tissue throughout the female reproductive system and an excess has been associated with many hormone driven diseases including breast and prostate cancer, as well as endometriosis.

While most oestrogen is excreted via the urine, some is excreted in the bile, and into the intestines. This influences the makeup of the gut microbiome which is a key regulator of levels of oestrogen circulating in the body.

A subset of the gut microbiome, known as the ‘estrobolome’, is involved in metabolising oestrogen in the intestines. In dysbiosis, alterations to the estrobolome may result in more oestrogen being reabsorbed, instead of being excreted in the faeces. Consequently, there is higher circulating oestrogen, which may be a driver of endometriosis.

Managing Endometriosis

Medical management of endometriosis involves hormonal manipulation and/or other medications for symptom control. In severe cases, surgical removal of endometrial deposits may be recommended. Side effects are common, and the recurrence rate is high.

Fortunately, there are dietary and lifestyle interventions which are relatively simple to adopt. These, along with personalised natural medicine, are aimed to promote a healthy microbiome, support immune and gut health, correct hormone imbalances, and reduce inflammation.

Key considerations for women with endometriosis include:

- stress reduction and stress management techniques,

- an anti-inflammatory whole foods diet rich in fibre, and fermented foods

- adequate exercise

- adequate quality sleep

- herbal medicines, and

- targeted nutritional supplements.

A personalised approach focussing on optimising these factors may help to reduce symptoms and improve quality of life for women suffering from this condition.

Book an appointment to see Emma to discuss how a natural medicines approach can help you with your endometriosis.