What does it take to have strong and healthy bones?

Ultimately – excellent lifestyle and nutrition. In an ideal world we would all be extremely active through our growing years which is the time that bone is laid down for the future. Good nutrition and avoiding bone disorders, does not equal drinking loads of milk – in fact some studies have shown higher rates of hip fracture (a measure of severeity of osteoporosis in a population) in countries with the highest milk intakes. Good nutrition is more than taking calcium supplements or consuming a high-calcium diet. One problem with such strategies is that they can lead to stone formation in the gall bladder or kidneys, calcification on the artery walls (leading to cardiovascular disease) or the formation of bone spurs.

A wide range of problems can interfere with and adversely affect bone health, bone development and healing.

A variety of tests are available that can identify and track problems and progress.

The tests we most commonly use or recommend are:

- Osteoporosis markers – Urinary Telopeptides (measures bone-breakdown) – has a number of advantages over bone density scans.

- Salivary hormone testing – more accurate than blood tests for assessing hormonal imbalances

- Hair mineral testing – provides very comprehensive report on your mineral status.

- Body acidity testing. An overly acidic body tends to break down bone and have more difficulty remineralising bone. System acidity is most conveniently measured by urine testing. Your practitioner will give you goals and guidelines to reduce your system’s acidity.

You can be sure that the approach taken to you and your bone condition will be individualised for you – hence we do not make any broad recommendations.

What Kind of Bone Issues Can We Help?

In our clinic we offer nutritional therapy for the following:

|

|

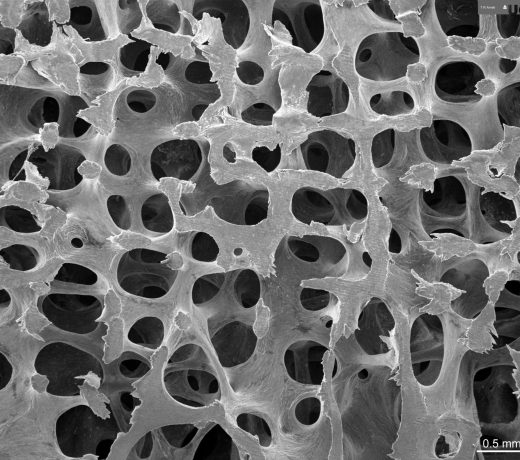

Normal Bone Structure

Bones, microscopically, are a matrix made up of a mix of calcium, magnesium, phosphorus and boron plus many other factors including collagen.

Hip Replacement

A complication of severe osteoporosis is a broken hip. Early intervention with individualised nutritional therapy can avoid the need for hip replacement surgery.

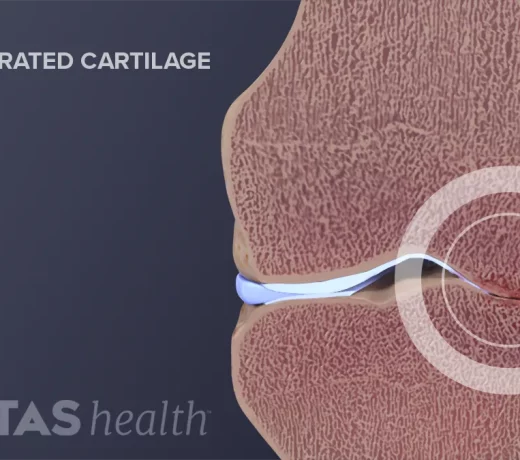

Degenerative Arthritis

Also known as degenerative joint disease, osteoarthritis occurswhen the cartilage (smooth connective tissue that linesthe ends of the bones where they meet) breaks down. This breakdown leads to pain, stiffness and swelling

Bones at Work

For skeletal growth and maintenance, the body’s 206 dynamic, living bones renew themselves throughout your whole life through a continual breakdown, build-up process known as remodeling.

In remodeling, complex chemical signals prompt cells called osteoclasts to break down and remove (resorb) old bone, and others called osteoblasts to deposit new bone.

Many elements influence remodeling. Among them: weight-bearing, vitamin D, growth factors, prostaglandins, and various hormones, including oestrogen, thyroid, parathyroid, and calcitonin.

As 80 percent of the mature skeleton, compact cortical bone supports the body, providing extra thickness mid-shaft in long bones to prevent their bending. Cancellous bone, whose porous structure with small cavities resembles a sponge, predominates in the pelvis and the 33 vertebrae from the neck to the tailbone. A fibrous membrane called the periosteum covers bone.

For healing and health, living bone must have a steady supply of nutrients. Blood vessels permeate bone to provide this lifeline. Blood-forming elements fill the long bone inner canals.

What Happens when a Bone Breaks

A fracture is the break in continuity of bone and involves damage to important attached soft tissue–including blood vessels, which spill their contents into surrounding tissue.

The body automatically seeks to repair the injury. Inflammatory cells rush to destroy, dilute or isolate invaders and injured tissue. Tiny new blood vessels called capillaries begin growing into the site. Cells proliferate. The injured person usually must endure pain, swelling, and increased heat at the breakage site for one to three days.

New tissue bonds the fractured bone ends with a soft callus, a mass of connective tissue and exudate (matter escaped through blood vessel walls). Remodeling begins. Within a few months, a hard callus replaces the soft one. Remodeling restores the inner canal.

Once restoration is complete, which may take years, the healed area is brand new, without a scar. Usually thicker, the new bone may even be stronger than the old, Yahiro says, adding that if the bone should break again, it’s unlikely to be at the same place.

Children’s bones have a healing boost: They’re growing. A very young child’s wrist bones grow a millimeter a month, to rapidly correct misalignment or length defects. An adult may take six to eight weeks to heal a wrist fracture, whilst in a 5-year-old this can heal in just three weeks.

Boning Up

The most important influences on bone health are nutrition and overall health.

In general, genes decide bone shape and size. But mechanical stress by muscle, body weight, and physical activity influence bone shape and density–and health–throughout life.

Simply put, loaded (stressed) bone strengthens, and unloaded bone weakens. As examples, astronauts’ bones weaken in outer space with no gravity pull on them, and the shaft of the humerus (long upper arm bone) in a professional tennis player’s dominant arm gets denser and thicker from the extra load.

The body increases its bone mass until, usually, the mid-30s, after which a gradual loss begins.

Age-related bone loss can lead to osteoporosis, a condition of thin, weakened bone that fractures easily. The condition affects many postmenopausal women, because bone loss increases with menopause due to lower oestrogen levels. We offer an excellent test that assesses your current rate of bone breakdown – click here for more information.

Unfortunately the common prescription medications, like most chemical substances, can have significant side-effects, or carry long-term risks. For example, Osteo-500 (prescription calcium) and Fosamax (routinely prescribed when low bone mineral density is diagnosed) carries a high risk of causing gastro-intestinal problems.

- Read more here

- Get started on your individualised Better Bones program today – start with a comprehensive health, nutrition and lifestyle consultation and get your osteoporosis markers test underway.