There is a gut-brain axis. But does this mean that gut health can influence, or worsen depression?

A growing body of research says that gut health and mental health are more closely linked than you might think.

Major depression is one of the leading causes of disability, morbidity, and mortality worldwide. People with a depressed mood can feel sad, anxious, empty, hopeless, helpless, worthless, guilty, irritable, ashamed, or restless [1]. Medical treatments for depression target the brain, with different drugs and/or psychotherapy. However, studies in recent years indicate that the gut microbiota could be a direct cause for the disorder [2].

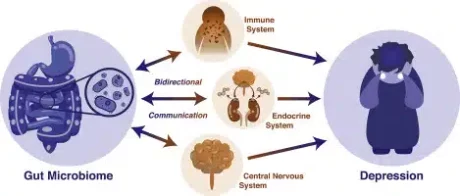

An imbalanced gut microbiome – also known as dysbiosis – and dysfunction of the so-called microbiota–gut–brain axis may cause mental disorders, and possibly correcting these disturbances could improve mood [2]. Disruptions to the gut microbiome have been correlated with several neuropsychiatric disorders, including depression[3].

Nowadays, the alteration of the gut microbiota has become a hot topic in research into the treatment of mental disorders. Interestingly, depressed patients often have gut-brain dysfunction, such as altered appetite, metabolic disturbances, functional gastrointestinal disorders, and gut microbiota abnormalities [3,4,5], all pointing to a close connection between gut health and mental health.

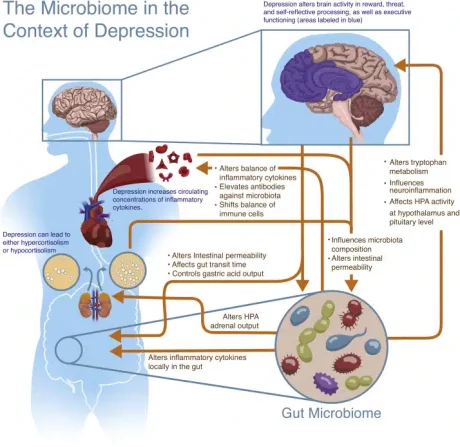

Image credit: Flux & Lowry (2020), Neurobiology of Disease [18]

The Human Gastrointestinal Tract

The human gastrointestinal system (the gut) is an incredible creation – it even has its own nervous system, called the enteric nervous system. This explains why we may feel “butterflies in our stomach” or experience a (sometimes urgent) need to go to the bathroom when we feel nervous. In addition, there are trillions of live bacteria in our digestive tract, making up our microbiota.

There is a complex cross communication between these microbes and the brain [6]. The two systems are connected physically and biochemically in several different ways. One of these interactions can be referred to as the gut-brain axis, which links your nervous system to your gastrointestinal tract. The role if this gut-brain connection is to link the emotional and cognitive centres of the brain with intestinal functions such as immune activation and intestinal integrity [7].

The Vagus Nerve and Neurotransmitters

Neurons are cells found in your brain and central nervous system that tell your body how to behave. Interestingly, your gut contains millions of neurons which are connected to your whole nervous system.

The vagus nerve is one of the biggest nerves connecting your brain and gut. Signals are sent in both directions. For example, stress inhibits the signals sent through the vagus nerve and can cause gastrointestinal problems and exacerbate symptoms of depression [6]. Hence, the vagus serves as the axis establishing the gut-brain axis phenomena.

Your gut and brain are also connected through signalling chemicals called neurotransmitters. Certain neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, serotonin, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), control emotions and feelings and are produced in the brain [8].

Interestingly, many of these same neurotransmitters are also produced by intestinal cells and by microbes living in your gut. For example, the serotonin, which contributes to feelings of happiness, is produced both in the brain and the gut [8]. When certain neurotransmitters are in short supply, it may lead to the symptoms we recognise clinically as depression. Learn more about the Vagus Nerve here.

Depression, Dysbiosis and Diet

It may be no surprise to know that the food you eat interacts with the gut microbiome. Diet-driven alterations in the gut microbiome can contribute to behavioural changes that mimic common symptoms associated with depression [9]. So with a good diet comes positive effects on gut health and mental health.

The Gut Microbiota of People with Depression Differs from those who are Not Depressed

Research demonstrates a clear connection between the brain and the gut, physically and biochemically. Psychological stress can change the composition of the gut microbiota, and in turn, microbiota abnormalities can influence emotional behaviour via the gut-brain axis [10, 11]. So, yes – it appears that your gut health and mental health are well connected.

Image credit: Flux & Lowry (2020), Neurobiology of Disease [18]

Probiotics

Probiotics are defined byt the World Health Organisation (WHO) as “live bacteria, that when taken in sufficient amounts, render a health benefit to the host”, and they have become increasingly popular. You might already be eating a lot of probiotic foods, such as yoghurt or sauerkraut, or take a probiotic supplement to reap their potential benefits.

In recent years, some experts have turned their attention to the relationship between certain probiotics and depression.

Specific strains of probiotic bacteria could potentially help a range of mental health conditions, including depression, and boost overall mood. In particular, it has been reported that some strains of probiotics play a major role in the bidirectional communication between the gut and the brain [13].

Experts believe that microorganisms living in your gut, including probiotics, play a crucial role in the gut-brain-axis by:

- producing and expressing neurotransmitters that can affect appetite, mood, or sleep habits,

- reducing inflammation in your body, which can contribute to depression [14],

- affecting cognitive function and the stress response

The Role of Probiotics in Depression

In a small study conducted in 2016, people with major depression were asked to take a supplement containing three strains of probiotic bacteria for eight weeks. By the end of the study, most had lower scores on the Beck Depression Inventory, a common method of evaluating depression symptoms[16].

In 2017 a review of research that had investigated the effect of probiotics on symptoms of depression found that taking a daily probiotic supplement seemed to help with anxiety, as well as depression [17].

The authors of these studies generally agree that larger trials are needed to understand how probiotics can affect symptoms of depression and other mental health conditions. Probiotics are a promising potential treatment for depression and other mental health conditions – improving both gut health and mental health.

Supporting Mood with Probiotics

If your mood is low, it is important to talk to a health practitioner who is well-equipped to identify abnormal alterations in mood.

A gut microbiome assessment can reveal the degree of dysbiosis in your gut microbial community and provide your practitioner with important guidance for supporting an individualised strategy to get your microbes back in balance. A holistic approach includes acknowledged that gut health and mental health are intricately connected.

If you have severe depression, have lost interest in the things that you used to enjoy or have suicidal thoughts, contact your doctor or therapist.

You can also call Helpline anytime, to speak to a trained counsellor.

phone 0800 543 354 (0800 LIFELINE) or free text 4357 (HELP).

The Role of Diet in Depression

Both short-term nutrient intake and long-term dietary patterns are recognised as important factors in shaping the diversity, composition, and metabolic function of the gut microbiota.

The effect of individual nutrients (such as fibre, polyunsaturated fatty acids and polyphenols) on brain health may be mediated by how they affect the microbiota and thus the gut-brain axis. For example, acetate and butyrate (short-chain fatty acids), produced by the gut microbiota by fermentation of dietary fibre, have been shown to play an important role in the correct functioning of the brain [12].

10 Tips for your Gut Health and Mental Health

Here are ten very cost effective things you can start doing right away to improve your mental health.

- Consume a healthy diet with 5+ servings of vegetables and 2 serves of fresh fruit each day

- Spend time outside – ideally in the sunshine

- Get your vitamin D tested – especially if your mood tends to be lower in winter.

- Exercise. Just walking for 30 minutes each day is good for your mood

- Turn off the news. Most news and lots of posts on social media have a negative effect on your mood. Switch it off.

- Reduce your alcohol consumption. Alcohol is a depressant all by itself.

- Talk to a friend. A problem shared is a problem halved.

- Do something that makes you laugh.

- Set goals and stick to them.

- And above all else, be kind to yourself.

While there is (so far) no research showing that probiotic foods have direct effects on mood, adding them to your diet can promote a healthy microbial balance.

- Yoghurt

- Kefir

- Kombucha

- Tempeh

- Miso

- Sauerkraut