What is Lactose?

Before exploring lactose intolerance, it’s good to understand lactose.

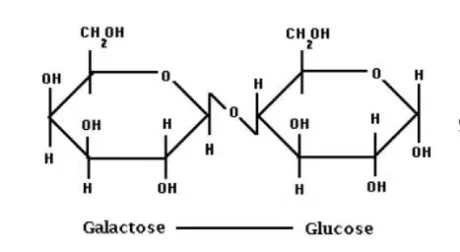

Lactose is the sugar the is naturally found in animal milk (cow, goat, human, etc). It is a disaccharide. That means it’s two (di-) sugar (saccharide) molecules joined together. These are glucose and galactose, which are both monosaccharides (single moleucules). But the lactose double-molecule poses a bit of an obstacle in the gut, as a disaccharide is too big to be absorbed.

Enter the solution: An enzyme, called lactase, is produced by humans, right there in the lining of the intestine. It is specific for breaking the bond that joins the two sugars that make up lactose.

What is Lactose Intolerance?

Simply put, lactose intolerance is when a person gets symptoms from consuming lactose. It can happen for two main reasons.

- A deficiency of lactase

- An infection or overgrowth of bacteria in the small intestine

Lactase Deficiency

The lactose content in cows milk is between 4.8% and 5.2%. The ability to produce lactase, to digest this, is encoded in your genes. While it is normal for everyone to be able to digest lactose (it’s in human milk), some people have a genetic defect of the LCT gene meaning that they cannot tolerate lactose, even from breast milk.

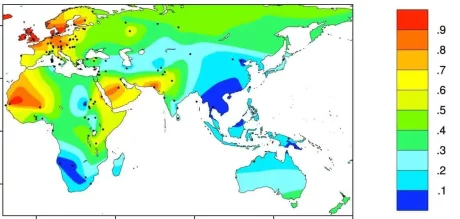

Lactase persistence is the term used to describe the continued ability to produce the enzyme, and therefore digest lactose after weaning, and often throughout one’s life. Lactase persistence is more common in societies where dairy animals were domesticated and consumption of their products became part of the diet.

Some ethnic groups, in particular those of Asian, Middle Eastern and Mediterranean decent, are more likely to lose the ability to digest lactose, and therefore develop lactose intolerance. It is very uncommon for those of European descent to develop it.

Lactose is a disaccharide (2 sugars), made up of glucose and galactose

Global lactase persistence. Red indicates high percentage of the population with lactase persistence, and dark blue is the lowest, where lactose intolerance is more common.

Source: BMC Evolutionary Biology

Other Causes of Lactase Deficiency

Because lactase is produced in the lining of the small intestine, right where it is needed, any condition that damages this lining can increase the chances of lactose intolerance. Examples of conditions where this damage might be an issue include coeliac disease, infection (and inflammation) in the small intestine, and Crohn’s disease (where it affects the small bowel). When the lining of the small intestine is inflammed or damaged, the enzyme cannot be produced. If the underlying problem is addressed and the gut heals, lactose is usually able to be consumed again without problems.

Bacterial Overgrowth in the Small Intestine

A variety of normal co-habitant bacteria (but not all) also have the ability to digest lactose. While the normal home of our microbiome is the large intestine, no appreciable amount of lactose gets there – at least not in a person with lactase persistence. But in some people there is a “proximal migration” of gut bacteria, meaning they establish themselves in the small intestine. And if these bacteria are able to digest lactose, symptoms can arise with lactose consumption.

What About Yoghurt?

Properly made yoghurts are produced by adding bacterial cultures to milk. These cultures are typically of the Lactobacillus family, and they ferment lactose, effectively removing it from the yoghurt. This happens in other fermented dairy products, such as quark, and kefir as well. There is also no appreciable lactose in well-cultured cheeses, as again, the bacterial cultures have digested these sugars.

What are the Symptoms of Lactose Intolerance?

The symptoms of lactose intolerance can seem to be similar to irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). For example:

- Frequent (but possibly intermittent) diarrhoea

- Flatulence (farting lots)

- Abdominal bloating

- Abdominal pain

These symptoms are aggravated by consumption of products containing lactose. One problem is that milk products are also used in a lot of non-milk items (such as bread), and lactose is used extensively in the making of medicines. So it is easy to be consuming small amounts without realising it.

How is Lactose Intolerance Diagnosed?

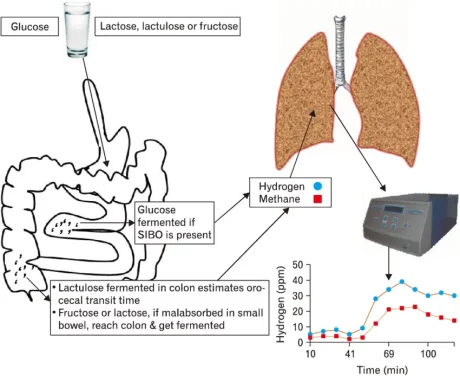

For a definitive diagnosis, a lactose breath test is conducted. An increase in breath gases following ingestion of a test-dose of the sugar, will occur if the sugar has not been broken down and absorbed. This increase in gases on the breath occurs due to the sugar being fermented by bacteria in the small intestine (where an overgrowth there has occured), or upon reaching the large intestine intact, due to a deficiency in lactase.

A small bowel biopsy taken during a gastroscopy (a medical procedure where a tube and camera are inserted via the mouth, passed into the stomach and upper part of the small intestine) can determine the prescence (or abscence) of the lactase enzyme in the lining of the small intestine.

A genetic test can dtermine a defect in the LCT gene, and related genes, such as MCM6. SNPs on these genes are also predictive of lactose intolerance.

A Hydrogen-Methane Breath Test is used to Diagnose Lactose Intolerance, after ruling out Bacterial Overgrowth.

How is Lactose Intolerance Treated?

How the problem is managed depends on the reason for the intolerance. Initially, lactose avoidance will eliminate symptoms, where lactase deficiency is the key problem. Supplementing with lactase enzyme can improve tolerance to lactose in food when it can’t be avoided.

If an inflammatory process is damaging the small intestine, then addressing the cause of that, and healing it, is expected to result in the return of th ability to consume dairy products without symptoms.